Challenging Constant Change in the Nonprofit Sector

If you recognize yourself in the words “founder” or “innovator” and you work in the nonprofit sector, you may be a lot like me. You have started at least one organization in your life or put a significant amount of money to fund an organization to do something about whatever is eating at you. The slow pace of change also eats away at you. You have a bias toward immediate action. When you feel despair at all that’s wrong with the world you combat it by looking for something to fix. You are, in fact, driven — sometimes frenetically — to fix things. All the things. ALL THE TIME.

You are a change-insister. You fight the good fight against the change-resisters and the status quo every day of your life. And if you’re like me (and I am very much like all of these things I just described) it may be hard to slow down for even one second, because there’s just so much to do and so much that needs fixing. We are encouraged at all turns to keep innovating, keep pushing, keep changing.

The problem with the fetishization of constant innovation is we’re often swept into the next big idea before allowing the changes from the last one to take root or provide valid information to guide the next change. I believe the obsession with innovation and frenetic action is stopping our sector from achieving the real, deep changes it needs to bring about in the world. So as one change-insister to another, I want to offer you a new way to see our roles and the trajectory of the organizations we run, fund, and push toward the future.

The Life-Changing Graph (tm) —My Story

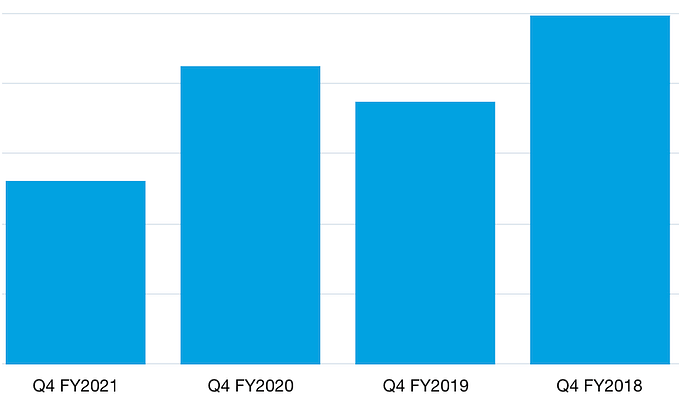

As a change-insister, I used to get righteously angry at the change-resisters who couldn’t — or in my old mental model, didn’t want to — keep up with what I felt was the necessarily rapid pace. Somewhere mid-2018, thinking about some other problem entirely, I sketched up my life-changing graph and got a good look at why my desire for constant change may be doing the opposite of what I want, and why people like me and my founder friends are often accused of causing “whiplash” for the people we’re collaborating with to implement big ideas.

My Life Changing Graph is completely unscientific. It isn’t, actually, a graph, not in any formal sense of the word. But I always draw it like this because it shows how it feels to go through some kind of big change. It is a representation of decision volatility (frequency and number of changes in decisions) as you become increasingly familiar with basically anything. New company? This graph applies. Moved to a new city? This graph applies. New project at work? This graph applies. Thinking about the trajectory of your life? Strong possibility this graph applies.

I have an unusually strong preference for progressing through the innovation and implementation parts of the graph. My professional expertise is in shepherding groups of people on the often bumpy journey from innovation through implementation. I have also lived in maintenance enough that the experience shapes and improves how I build solutions, but I still prefer to flee that territory as quickly as possible when I have the choice.

I have been guilty of (unintentionally) doing my utmost to keep the whole organization in my comfort zone — forever moving through innovation and implementation, never touching down in maintenance. My comfort zone causes people to spend a lot of energy regaining their bearings if it doesn’t happen to overlap their comfort zones. Big surprise, this isn’t a pleasant experience for anybody. I had to learn to respect the reality that change takes time to navigate when many people are involved — even highly-motivated, energetic, can-do people who aren’t actually change-resisters. What works for me navigating change by myself can’t work for a large group of people navigating change at the same time. It’s the flip side of “if you want to go fast, go alone; if you want to go far, go together.”

Graphing Projects and Organizations

Organizations, programs, and projects go through a lifecycle that begins with invention and moves through implementation toward maintenance. You may be more familiar with the terms early-stage (or start-up), maturing (or scale-up), and mature. As a founder or someone tasked with innovating or implementing new programs or projects, you’ve lived through at least the first phase of this graph, but the maintenance phase may not be territory you’ve had much time to explore. In the nonprofit world in particular, many organizations never get more than mid-way through implementation before they’re shoved back into invention mode.

There are many forces that prevent nonprofits from reaching maintenance or maturation. Time-limited funding and philanthropy’s general preference for funding new ideas are big contributors to this situation. I believe that internal change-insisters — like founders and board members — also unintentionally keep organizations in early stage activities. I’ve heard so much animosity toward the ideas of maintenance and maturity in my travels through the sector. Perhaps we think if we make it to maintenance or maturity we’re just doing it wrong. We equate maturity with bloat, waste, and bureaucracy, possibly because many of us have never seen a place where maturity means stability, confidence, effectiveness, efficiency…and the opportunity to innovate at a totally different level.

Graphing the Learning Process

When you innovate at your organization, you’re asking your organization to learn. Learning is basically adapting to change, and looks like the image below. Spoiler alert: it’s the same graph with different words!

Every time you pick up something new — new hobby, starting a new company, or introducing an innovation or improvement — you’ll be a beginner for awhile. Even if you think you have a really clear idea of how everything should go, no plan survives contact with the world. During your early learning phase, you’ll screw up a lot. You’ll figure stuff out and then mis-step the very same day. All early stage learning looks like this, even with systems or technologies or business models or services someone else has already figured out. It was figured it out in a different context. You still have to go through this cycle to apply it to your context.

In a new company, or while launching a new program or project, everybody in the organization processes change by living out their own individual graphs. When two people have to work together during this time they risk dramatically amplifying the volatility — they wind up confusing each other because things are simply too new. If one or both has figured out something that works, they can teach each other and damp down the volatility. It takes time, tremendous energy, and attention to allow a change to work its way through an organization correctly.

Over time and with repetition everyone makes fewer mistakes and figures out the basics. They come through the worst of the volatility and are able to confidently perform the 60–70% of tasks that are required for normal, every day operations. They leave “novice” and move to “intermediate.” There are still things that cause stress and mistakes, but they can solve these problems faster and more confidently because their attention and energy isn’t dedicated to the basics anymore. With enough time operating in a predictable and stable environment, the majority of problems are solved and the organization can begin to optimize activities, gain efficiency, and use trusted data to identify areas for improvement or that need renovation.

Constant change = never mastering anything

Now look again at the two graphs. In our organization or project lifecycle, the right-hand side of the graph is labeled “maintenance” — which most of us on Team Fix It Now think of as a boring, slow, bureaucratic hell to be avoided at all costs. The not-so-surprising plot twist? Maintenance and the path to mastery (or stagnation) are the same phase. Organizations can choose which path defines their maintenance phase.

Maintenance does not have to usher in stagnation; it can also facilitate big breakthroughs. The difference is in how energy and attention are used and focused during that time. If people are allowed to stop paying attention, or encouraged to spend their energy on inconsequential things, bureaucracy flourishes. If people are allowed to use their expertise to inform change initiatives from a place of strength and deep insight, innovation can occur. As a leader, you can help your organization choose the path to mastery.

Purposeful or mindful ongoing practice is the key to mastery, which is also the key to true innovation from a position of strength. The great innovators in every field — musicians, writers, scientists, visual artists, you name it —first mastered their practice of the rules so they know exactly how to break those rules. The innovations that Newton and Einstein ushered in have staying power because they were not novices in their fields. They knew deeply what they didn’t like or what didn’t make sense about the systems they’d learned, and they upended those systems. Today, Newton’s and Einstein’s work form the rules that this generation of innovators are seeking to upend. These innovators are able to create enduring change because they didn’t stop paying attention to the details, questioning, or making decisions after they got through the first two phases.

Repetition without reflection becomes bureaucracy. Most of us learned some of those same rules that Newton and Einstein also started with. Take multiplying two numbers, for example: most of us solve that problem by applying memorized rules without any critical thought. We memorized it and stopped paying attention or asking questions. Someone who has mastered mathematical principals thinks about multiplication as a reflection of fundamental patterns that can be rigorously proven and used to deduce other, new fundamental patterns.

When leaders in the nonprofit space prevent organizations from moving into maintenance mode out of fear of stagnation, we actively block people from learning enough to make the lasting changes we’re trying to achieve.

Please stop forcing organizations into novice mode!

No one is intentionally wreaking operational havoc in the nonprofit space. We think we’re doing the right thing by “keeping it lean”, reacting quickly when initiatives don’t show enough progress, and other practices that make intuitive sense to my fellow founders and status-quo-shakers. Sometimes we’re absolutely right to do so. But maybe sometimes we’re not so much.

I make my living doing the digital equivalent of designing, architecting, contracting, and sometimes hands-on building houses and neighborhoods that I will never live in. I have to make sure the people moving into those houses are safe living there, proud to live there, and fully able to do whatever they need to do with their dwelling. Think about what would happen to the health, happiness and safety of the people in those homes if, every time they got done unpacking, someone forced them into temporary shelter while I razed the neighborhood and started over.

Because processes, technologies, and services — our organization’s operations — are not understood as the enduring support structures they actually are, it’s easy to think there’s no harm in tossing them out and starting over again. Every strategic change impacts this support structure, and big changes can destroy it entirely, leaving employees to rebuild while continuing to serve the organization’s constituents. Wouldn’t it be better if we allowed people to devote their full energy and attention to delivering on mission and engaging in the critical work of shaping effective, impactful changes from a place of expertise?

My purpose in this essay is to help my fellow change-insisters gain a different perspective on what it means to demand rapid or constant change in our organizations. If you are an unintentional chaos-maker, I hope to challenge you to re-envision your role in a way that satisfies your restless need to fix, question, and stay open to new information while allowing your organizations to develop the deeper learning necessary for informed and deep change. If you’re leading an organization on its path to mastery, I’d love to hear how you got there.

I’m an unlikely voice for the value of progressing toward stability, but embracing its value makes my design and consulting so much more effective that I’ve become an advocate. I have come to understand that the problem isn’t with the change-insisters or change-resisters. It’s with the blindness we each have toward each other’s role in letting a major change succeed. Some of us put pressure on organizations to change, and that’s valuable. Some of us put pressure on organizations to stabilize, and that’s valuable. Like everything else, we can only achieve real and lasting change when we use the differences to generate productive creative tension, and allow that tension to remain while we work through what we really want to bring to the world.

My Life Changing Graph (tm) first showed up in some work on the Data Maturity Model I did for 501Partners in 2018. It made its way into a blog of random thoughts I update sporadically. And then into the foundational theory of Deep Why. It changed my relationship with my career and freed me to appreciate on a deeper level how truly destabilizing change is for an organization, what that means at scale in the social sector ecosystem, and what role I can most ethically and effectively play. It’s a very useful mental model. I expect that by 2023 I will see how flawed and wrong it is and be ashamed to ever have made such a big deal out of it, because I will have moved to the right-hand side of the graph and I will be compelled to destabilize it.